Distal biceps tendon rupture

Introduction

Distal biceps tendon rupture once considered unusual, has become much more commonly recognized, in part because of an increased awareness of the injury.

Typically middle-aged males, weight lifting or in work related instances involving heavy lifting or forearm twisting.

Clinical

History

Sudden, sharp, painful tearing sensation in the antecubital region of the elbow when an unexpected extension force is applied to the flexed/supinated arm.

Occasionally pain is also present in the posterolateral aspect of the elbow.

The acute pain subsides in a few hours and is replaced by a dull ache.

With chronic ruptures, weakness and fatigue occur with repetitive flexion and supination.

On Examination

Tenderness in the antecubital fossa, and a defect can usually be palpated.

Beware the bicipital aponeurosis may remain intact and can be mistaken for an intact tendon.

The biceps is the main supinator of the arm and secondary flexor.

Active flexion and supination of the elbow causes the biceps muscle belly to retract proximally, accentuating the defect in the antecubital fossa.

If the biceps tendon can be palpated in the antecubital fossa, a partial rupture of the distal biceps tendon should be considered.

Bruising and swelling occurs in the antecubital fossa and along the medial aspect of the arm and proximal forearm.

Acute distal biceps rupture results in:

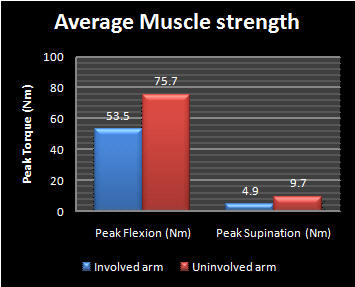

40% loss of supination strength

15% loss of flexion strength, the flexion strength loss decreases with time.

From

JSES 2009 This is average muscle

strength in arm following rupture of distal biceps, median time from injury 2.9

months, range (2weeks to 3 years)

From

JSES 2009 This is average muscle

strength in arm following rupture of distal biceps, median time from injury 2.9

months, range (2weeks to 3 years)

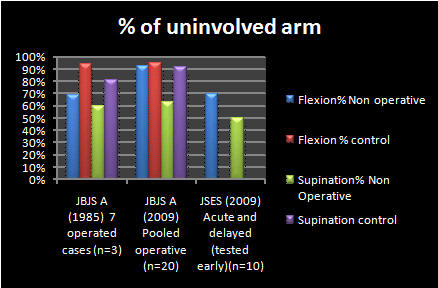

The deficit in maximal flexion strength reduces with time

-

70% flexion strength around 3 months (JSES 2009)

-

85% flexion strength after 1 year (JBJS 2009)

-

-

50% Supination strength around 3 months (JSES 2009)

-

75% supination strength after 1 year (JBJS 2009)

Patients often complain of a degree of fatiguability, the muscles do not themselves fatigue faster, the symptom of fatiguability is most likely related to the relatively lower maximal strength starting points.

Radiographs

Plain radiographs are required to exclude bony abnormality and normally show no abnormality, Irregularity and enlargement of the radial tuberosity and avulsion of a portion of the radial tuberosity has been reported.

Special investigations

MRI or ultrasound can be helpful to distinguish complete from partial ruptures and to differentiate partial rupture from tendinosis, tenosynovitis, haematoma, and brachialis contusion.

Treatment

-

Non operative

-

Operative

Nonoperative treatment

In elderly and those not fit for surgery.

Pain control and introduction of early range of motion when able.

Once full range of motion is established, strengthening begins, concentrating on supination.

Patients lose approximately 25–30% of their supination strength.

Flexion strength decreases acutely but improves to around only 15% loss after around 1 year from injury.

In some patients the pain does not completely resolve.

Once Range of motion restored question patients on all activities that are important to them.

If they are unable to perform any function, consider operative treatment.

Operative

Operative treatment is indicated in patients that cannot tolerate a loss of supination strength.

The patient risks:

-

Infection

-

Nerve damage

-

Wound breakdown

-

Stiffness

-

Continued pain

Historically, distal biceps tendon ruptures were repaired through a single-incision technique using drill holes in the radial tuberosity for reattachment.

These early repairs were complicated by difficult exposure to gain sufficient retraction to pass sutures through these drill holes and tie on the posterior aspect of the radius (Meherin).

As a result, posterior interosseous nerve and radial nerve injuries were quite common.

In 1961, Boyd and Anderson published their report on a two-incision technique for repair of the distal biceps tendon. This approach was developed in response to the high incidence of radial nerve injury associated with a single incision technique.

However, the two-incision technique was associated with different complications, such as heterotopic ossification and proximal radioulnar synostosis.

Morrey et al subsequently modified this technique, using a muscle-splitting approach to avoid contact with the periosteum of the ulna.

This decreased the incidence of heterotopic ossification or proximal radial ulnar synostosis.

Kelly et al

described a two incision technique using a mini anterior incision.

The development of suture anchors, endo buttons and interference screws has allowed the return to a single-incision technique through an anterior approach.

In order to perform a safe single incision technique, without the necessity of tendon graft or augmentation, the surgery should be done 1 to 4 weeks after injury.

If the patient is outside of this time period, the operative plan should include the potential for tendon graft or augmentation.

Deirmengian et al reviewed the literature 2006, the most commonly used approaches are:

-

2-incision modified Boyd-Anderson approach with transosseus suture fixation (Kelly, Drosdowech)

-

1-incision anterior approach with alternative fixation methods

-

Suture anchors (Galatz, Drosdowech)

-

Endobutton (Bain)

-

Endobutton and interference screw (Mazzoca)

-

The data available shows good to excellent results with both procedures and only relatively minor differences in outcomes.

Leaving the decision of repair

technique open to surgeon preference, surgeon training, and comfort level with

the approaches.

See approaches for:

References

Meherin JH, Kilgore BS Jr. The treatment of rupture of the distal biceps brachii tendon. Am J Surg 1960;99:636–8.

BAIN GI; Repair of Distal Biceps Tendon Avulsion With the Endobutton Technique; Techniques in Shoulder & Elbow Surgery 3(2):96–101, 2002

Boyd HB, Anderson MD. A method for reinsertion of the distal biceps brachii tendon. J Bone Joint Surg 1961;43A: 1041.

Morrey BF, Askew LJ, An KN, et al. Rupture of the distal

tendon of the biceps brachii. A biomechanical study. J Bone Joint Surg

1985;67A:418–21.

KELLY E W, O’DRISCOLL SW; Mini-Incision Technique for Acute Distal Biceps Tendon Repair; Techniques in Shoulder & Elbow Surgery 3(1):57–62, 2002

DROSDOWECH

DS, FABER KJ, KING GJW; Distal Biceps Tendon Repair: One- and Two-Incision

Techniques; Techniques in Shoulder & Elbow Surgery 3(2):90–95, 2002

Deirmengian G, Beredjiklian PK, Getz C, Ramsey M, Bozentka DJ; Distal Biceps Tendon Repair: 1-Incision Versus 2-Incision Techniques. Techniques in Shoulder & Elbow Surgery. 7(1):61-71, March 2006

GALATZ LM, JANI MM, YAMAGUCHI K; Single Anterior Incision Exposure for Distal Biceps Tendon Repair; Techniques in Shoulder & Elbow Surgery 3(1):63–67, 2002

Mazzocca AD, Bicos J, Arciero RA, Romeo AA, Cohen MS, Nicholson G; Repair of Distal Biceps Tendon Ruptures Using a Combined Anatomic Interference Screw and Cortical Button; Techniques in Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 6(2):108–115, 2005

Proximal radial fracture after revision of distal biceps tendon repair: A case report; Alejandro Badia, S.N. Sambandam, Prakash Khanchandani; Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery; March 2007 (Vol. 16, Issue 2, Pages e4-e6)

Elbow strength and endurance in patients with a ruptured distal biceps tendon.;

Nesterenko S, Domire ZJ, Morrey BF, Sanchez-Sotelo J.; J

Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009 Aug 5

Nonoperative Treatment of Distal Biceps Tendon Ruptures Compared with a

Historical Control Group; Carl R. Freeman, Kelly R. McCormick, Donna Mahoney,

Mark Baratz, and John D. Lubahn;

J. Bone Joint

Surg. Am., Oct 2009; 91: 2329 - 2334.

Rupture of the distal tendon of the biceps brachii. A biomechanical study;

Morrey BF, Askew LJ, An KN, Dobyns JH. . J Bone Joint Surg Am.

1985;67:418-21

Page created by: Lee Van Rensburg

Last updated: 11/09/2015